斯坦福 iOS7 公开课第四课:Foundation and Attributed Strings

这是 Stanford CS193p: Developing iOS 7 Apps for iPhone and iPad Fall 2013-14 文字版,按照视频字幕手工编辑完成。这里的内容由于是按照讲话的录音记录下来的,所以文字风格偏口语化,也比较”线性”. 视频的内容大部分会记录成文字,但也酌情省略了可以忽略的语句。本文更好的排班效果可看这里。

0. Today

Today we’re going to start off by talking about a little bit more miscellaneous Objective-C. And then I’m going to go into talking about Foundation, which is this framework that has arrays, and dictionaries and all that in it. And we’ll start to transition out of Foundation at the end of that and start talking about things like fonts and colors which are obviously not in Foundation because Foundation is really not a UI-based thing; it’s for building both your model, and your controller, and your view. But, it’s, you know, a layer below the user interface layer. #####More Objective-C

- Creating objects˝

nil- The very important type

id(and the concept of “dynamic binding”) - Introspection

- Demo (improving match: with introspection)

#####Foundation

NSObject, NSArray, NSNumber, NSData, NSDictionary, et.al.

Property Lists and NSUserDefaults

NSRange

UIFont and UIColor (not atually Foundation, they’re in UIKit)

NSAttributedString (and its UIKit extensions)

Attributed strings in UITextView and UILabel

1. Creating Objects

Let’s talk about create objects. A few of these things are pretty obvious I hope, but I just want to put them on slides so that you have them in writing here.

Most of the time, we create objects with alloc and init…

NSMutableArray *cards = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

CardMatchingGame *game = [[CardMatchingGame alloc] initWithCardCount:12 usingDeck:d];

Or with class methods

And you’ve also seen us create objects in the heap using class methods like string with format. Remember, we did NSString, string with format. And that’s a class method, right? Because it’s open squre bracket, name of a class, and then class method. So it gets kind of two different ways you’ve seen already to create objects.

NSString’s + (id)stringWithFormat:(NSString *)format, ...

NSString *moltuae = [NSString stringWithFormat:@“%d”, 42];

UIButton’s + (id)buttonWithType:(UIButtonType)buttonType;

NSMutableArray’s + (id)arrayWithCapacity:(int)count;

NSArray’s + (id)arrayWithObject:(id)anObject;

Sometimes both a class creator method and init method exist

Sometimes for some methods, there’s both an init and a class method. So string with format is an example that there’s alloc init with format and there’s NSString, string with format. They do exactly the same thing. Both of them are there for kind of historical reasons. Back before we had this automatic reference counting – you know, the strong and weak thing – you had to be much more explicit about things when you were going to, you know, reference them, and when they got dereferenced, and when you cleared them out of the heap, and all that stuff. And one of the ways that was done was using these class methods to create the string in a way that it would get released in certain ways.

It’s seems to me that iOS, the designers at Apple – I don’t work at Apple, by the way–So I’m just seeing iOS from the outside just like you are. It looks to me like iOS people are moving towards alloc init, okay, and kind of away from the class methods. Although I still see the class methods coming up in certain circumstances, and there’s probably some reasoning behind it. I haven’t seen it put in writing by Apple as to when they choose which, but you’re certainly safe in this class until they start marketing some of these things as deprecated, like, don’t use them anymore, to use either form, okay? I tend to try to go for the alloc inits most of the time unless there isn’t an alloc init that does what I want;

[NSString stringWithFormat:...] same as [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:...]

Don’t be disturbed by this. Using either version is fine.

iOS seems to be moving more toward the alloc/init versions with new API, but is mostly neutral.

You can also ask other objects to create new objects for you

But there’s other ways to create objects. You can create objects by asking another object to create an object for you. So that’s like string by appending string. That’s not a class methods in string. You send it to another string, you give it a second string, that’s an instance method, and it will create a new string for you since strings are immutable. NSString is immutable. It create a new string that is the string you sent it to with the one you passed as an argument added on, right? So there it’s creating a new object for you, okey? And a very interesting instance method that you can ask an object to do for you is mutable copy, okey? So mutable copy makes a copy of an object but it’s mutable. So if you had an NSString and you send it mutable copy, you’ll get back an NSMutableString. Or if you have an NSArray and you send it a mutable copy, you’ll get an NSMutableArray.

NSString’s - (NSString *)stringByAppendingString:(NSString *)otherString;

NSArray’s - (NSString *)componentsJoinedByString:(NSString *)separator;

NSString’s & NSArray’s - (id)mutableCopy;

But not all objects given out by other objects are newly created

Of course, not all methods that return an object are creating an object like we saw in NSArray – last object, and first object, and object at index. Those aren’t creating new objects; they’s just giving you pointers to the objects that are in those array. And you’ve allowed to have multiple pointers. And this is normal pointers here being passed around. Okay?

NSArray’s - (id)lastObject;

NSArray’s - (id)objectAtIndex:(int)index;

Unless the method has the word “copy” in it, if the object already exists, you get a pointer to it. If the object does not already exist (like the first 2 examples at the top), then you’re creating.

###2. nil #####Sending messages to nil is (mostly) okay. No code executed. However, that message sending square bracket thing will return zero. If the method returns a value, it will return zero. Zero is also what nil is. So if you had a method that returned an object and you sent that message to nil, then you get back nil.

int i = [obj methodWhichReturnsAnInt]; // i will be zero if obj is nil

If’s definitely different from other langages where you’re protecting against sending messages to nil. You do have to be careful if the return type of a message send is a struct, because you don’t get back a struct with all its members set to zero; you get back an undefined struct. Okay? What’s in there is undefined. Okay? This struct is being returned to you on the stack. You might get stack garbage, you might get zero.struct, you just don’t know. So you can’t rely on it. So here you should never rely on that in you code. Okay? If you call a method, it returns a struct, you got to chech to make sure you’re not sending it to nil.

CGPoint p = [obj getLocation]; // p will have an undefined value if obj is nil

3. Dynamic Binding

#####Objective-C has an important type called id Objective-C handles the dispatching and calling of methods differently than most of you are used to. It does what’s called “dynamic binding.” Okay? And you’ll see what dynamic binding is as we go through this slide. But the important thing to understand about dynamic binding and about Objective-C is that there’s a really, really important type in Objective-C called “id”, okay? So here in that line of code I would say that:

id myObject;

I’m declaring a pointer, myObject, which is a type id. So id means pointer, id is a pointer, so we don’t use id *, it means a pointer to an object where I don’t know its class. Okay? Of unknown type or unspecified type, okay? So it’s just a pointer to an object; I do not know anything about that object.

Really all object pointers in Objective-C are ids, in that the decision about what code to execute when you send a message to an object is not determined until runtime when you send that message. Okay? When you send a message, it’s essentially calling a function that’s looking up the right code to execute for that particular class that you’re pointing to at the time you send the message, okay? That’s called dynamic or late binding, okay? And all message sends – all of them in Objective-C are done this way, okay?

But at compile time, if you type something NSString * instead of id, the compiler can help you. It can find bugs and suggest what methods would be appropriate to send to it, etc. If you type something using id, the compiler can’t help very much because it doesn’t know much.

#####Is it safe?

What if I send a message to an object and it doesn’t understand it? Well, nothing stops you from doing that. And not only that, if you do that, your program will crash. It will raise an exception. Unless you catch the eception, it will crash. And so you’re probably feeling like, “Wow, These Objective-C programs must be crashing all the time, because you accidentally send a message to an object, it doesn’t understand that message.” But actually, it doesn’t happen. Okay, why doesn’t that happen? There’s really two reasons. One is we use static typing a lot. We don’t use id that much, we use, like, NSString star. Now, NSString star is exactly the same as using id, except that the compiler, while it’s compiling your code, knows that you at least intend that pointer points to a string. So if you tried to send a nonstring message to that pointer, it’s going to complain. It’s going to, you know, give you warnings. And so when you compile your Objective-C programs they should always have no warnings, and then you can be pretty sure that you’re not going to have this problem where you send a message to an object at runtime and it doesn’t understand it and it crashes. Okay? So that’s the number one way. And the second way I’m going to talk about is that a lot times we will check at runtime. We’ll look at that id pointer, okay? And we will check and see if it responds to something before we send it.

#####Static typing. So you know about static typing:

NSString *s = @“x”; // "statically" typed(compiler will warn if s is sent non-NSString messages).

This really safe, really good, nothing bad’s going to happen here because the compiler at compile time has a pretty good idea what you intend and it will warn you if not. However, the compiler is not doing the binding between what does executes at this time; it just warning you. It’s syntactic sugar. It’s syntax that it can look at to warn you, but it’s not actually enforcing anything here. It’s perfectly legal:

id obj = s;

s is the line before. And that will not even generate a warning. Because id obj is a pointer to any kind of object; s is pointer to any kind of object. It’s a pointer to a string, according to the previous line. But since those are both pointers to objects, that’s perfectly legal. Compiler will not warn you. This is a little bit of a dangerous line of code ,right? Because you just went from having s – this nice variable that’s typed and the compiler can warn you if you do the wrong thing – to have an obj, which is this untyped pointer where you can send any message you want and the compiler’s not going to warn you. You can also do this:

NSArray *a = obj;

Okay, now you have NSArray variable that points to a string. Now, that’s extremely likely to cause to problem, okay? This is also legal because NSArray *a is a pointer to an object, obj is a pointer to an object, so it allows this assignment. Very dangerous. Obviously wrong. So id can be dangerous in this way.

And in fact, in the code that we’ve written we already did this kind of silently. Remember that in playing cards match we put a line in there:

- (int)match:(NSArray *)otherCards

{

...

PlayingCard *otherCard = [otherCards firstObject]; // firstObject returns id!

...

}

Well, the method first object in an NSArray returns an id – if you go look it up in the documentation, look at its return type – parenthesis id. So we just assigned a playing card to an id. So that object that came out of that array better be a playing card or we’re going to crash at runtime. And a little later in this lecture I’m going to show you how we can protect our code to make sure that we don’t crash in this case. And a reminder: Never use id *. id * makes no sense, because id is a pointer. So id * would be a pointer to a pointer. We don’t do that in Objective-C.

###4. Object Typing So to summarize all this I’m going to show you this example. I’ve got two classes, I got a vehicle class, which has what method move – you can move the vehicle around – and I got a ship which is a vehicle, inherits from vehicle, and it’s only got one method, shoot. So this ship can shoot other ships. And they also move because they’re vehicles.

@interface Vehicle

- (void)move;

@end

@interface Ship : Vehicle

- (void)shoot;

@end

Ship *s = [[Ship alloc] init];

[s shoot];

[s move]; //No compiler warning. Perfectly legal since s “isa” Vehicle. Normal object-oriented stuff here.

Vehicle *v = s; //No compiler warning. Perfectly legal since s “isa” Vehicle.

[v shoot]; //Compiler warning! Would not crash at runtime though. But only because we know v is a Ship. Compiler only knows v is a Vehicle.

id obj = ...;

[obj shoot]; //No compiler warning. The compiler knows that the method shoot exists, so it’s not impossible that obj might respond to it.

//But we have not typed obj enough for the compiler to be sure it’s wrong. So no warning. Might crash at runtime if obj is not a Ship (or an object of some other class that implements a shoot method).

[obj someMethodNameThatNoObjectAnywhereRespondsTo]; //Compiler warning! Compiler has never heard of this method. Therefore it’s pretty sure obj will not respond to it.

NSString *hello = @”hello”;

[hello shoot]; //Compiler warning. The compiler knows that NSString objects do not respond to shoot. Guaranteed crash at runtime.

Ship *helloShip = (Ship *)hello; //No compiler warning. We are “casting” here. The compiler thinks we know what we’re doing.

//So casting can be super dangerous, just like in any languages casting can be dangerous. It can be dangerous here. But we do do cast sometimes. And the times we cast are the same kind of times we use `id`, which is protected times. I'm going talk about that protection on the next slide.

[helloShip shoot]; //No compiler warning! We’ve forced the compiler to think that the NSString is a Ship. “All’s well,” the compiler thinks. Guaranteed crash at runtime.

// The typecasting really doesn't do anything; that is just tricking the compiler. That's not even executing really any code. It's when you send the shoot, it tries to dispatch that shoot to that variable, that hello variable. The thing turns out to be a string, and it crashes right here.

[(id)hello shoot]; //No compiler warning! We’ve forced the compiler to ignore the object type by “casting” in line. “All’s well,” the compiler thinks. Guaranteed crash at runtime.

// You can cast it right in line; you don't have to create another variable, you fake out the compiler. Now we don't want to be facking out the compiler. It helps us find bugs, compiler is our friend. But this all can be done. Mostly I put this up here to see the difference betwen the compiler catching something and it crashing at runtime, and when it does which.

###5. Dynamic Binding

#####So when would we ever intentionally use this dangerous thing: id!

When we want to mix objects of different classes in a collection (e.g. in an NSArray). When we want to support the “blind, structured” communication in MVC (i.e. delegation). And there are other generic or blind communication needs.

Someone asked earlier, “Can I have an NSArray that has different kinds of things in it. Some strings, some numbers, something else?” Absolutely you can. And there’s plenty of times when you absolutely want that, okay? So it’s great for that. Now, other language like Java lets you actually tell the compiler that this array has strings in it, so that the compiler, when you pull objects out, it knows what type they are and it can kind of help you out. Objective-C doesn’t have that. So the compiler cannot help you with contents array. Okay? It’s kind of your responsibility. I’m going to show you how we deal with that.

The second one is – remember the NBC talk(应该在 Lecture 1 的 MVC 讲解中)? I talked about all this blind strutured communication, right? Well, to have blind communication you got to have pointers to objects of types you don’t know. Okay? There’s no way that the view can send the target action thing to the controller without knowing the class of the controller, unless the view have some kind of pointer to a controller that it doesn’t know the type of. Okay? And that’s big use of id.

#####Introspection

However, we need to protect ourselves, and there’s two big ways that we protect ourselves against ids. One is introspection, which I’m going to talk about in the next few slides, which is we can ask an id at runtime, “What class are you?” or “What methods do you respond to?” So that’s a great way to protect oursleves.

#####Protocols

And then Another way is called protocols.

id <UIScrollViewDelegate> scrollViewDelegate;

And protocols is a way using little angle brackets after an id to say, “This is an id, a pointer to some class I don’t know what it it, but it responds to this set of methods that I’m going to define with this little angle bracket thing like UI scroll view delegate. “ And that’s how we do the delegation and data source thing. So we’re not going to talk about protocols today because you don’t quite need them. We’ll probably talk about them next week or the week after. But that’s another way we protect ourselves against id. An id with angle brackets is kind of in between pure id and static typing. It’s kind of in the middle. Instead of static typing the type, we’re just static typing the messages that the thing can respond to.

###6. Introspection Asking at runtime what class an object is or what messages can be sent to it. There’s a few introspection methods in NSObject. I’m going to talk about three of them here.

#####All objects that inherit from NSObject know these methods …

isKindOfClass: returns whether an object is that kind of class (inheritance included)

isMemberOfClass: returns whether an object is that kind of class (no inheritance)

respondsToSelector: returns whether an object responds to a given method

It calculates the answer to these questions at runtime (i.e. at the instant you send them). So isKindOfClass: and isMemberOfClass: lets you asking an NSObject or anything that inherits from NSObject, “Are you of this kind of class?” Or is member of class means, “Are you actually this class? Not something that inherits from it, but actually this actual class.” And then respondsToSelector: says, “Does this object that this id points to, does it repsond to a certain method?”

#####Arguments to these methods are a little tricky So the arguments unfortunately to these methods are really kind of wonky. And just you’re going to have to take my word for it on these ones because when I spit out the sentence in a second here that describes what the argument is, I’m going to use the word “class” four times and it’s going to mean four different things. Okay?

So the argument isKindOfClass: you get by sending the class method class to the class, which will give you a capital C Class, which is the argument to the isKindOfClass: method. Okay? So there’s this method class. You see it there:

#####Class testing methods take a Class

if ([obj isKindOfClass:[NSString class]]) {

NSString *s = [(NSString *)obj stringByAppendingString:@”xyzzy”];

}

It’s a class method on NSString returns a captial C Class. And that’s the thing that’s the argument isKindOfClass:. You get a Class by sending the class method class to a class (not the instance method class). It’s always of this form.

Once I see that an object kind of a class, then I might want to cast it. You see here I’m casting obj to be an NSString * there because I know at that point it’s an NSString *. So it’s okay to fool the compiler, or really I’m teaching the compiler a little bit more about what obj is by doing that. Not really tricking it. And it’s perfectly safe to do that.

#####Method testing methods take a selector (SEL)

How about the selector one, the method one rather. Okay, so methods, when we use them in this response to selector thing, we call them “selectors”. A seletor is really kind of an identifier for a method name, because if you have the method shoot, it’s the same selector no matter what class you’re talking about implementing it in. Even if they don’t inherit from each other, they’re completely unrelated. You might have a gun class that says shoot and you mignt have a ship class that says shoot – the selector shoot would be the same. Special @selector() directive turns the name of a method into a selector. And we get that selector by saying:

if ([obj respondsToSelector:@selector(shoot)]) {

[obj shoot];

} else if ([obj respondsToSelector:@selector(shootAt:)]) {

[obj shootAt:target];

}

#####SEL is the Objective-C “type” for a selector

These selector, there’s actually a type, kind of a type def in Objective-C for these selectors. All caps(大写) SEL, kind of like all caps BOOL, right? So this type def thing is added. And you can declare variables that are type SEL and store things in there.

SEL shootSelector = @selector(shoot);

SEL shootAtSelector = @selector(shootAt:);

SEL moveToSelector = @selector(moveTo:withPenColor:);

#####If you have a SEL, you can also ask an object to perform it …

And there are actually other methods besides respond to selector that take a selector. For example,

using the performSelector: or performSelector:withObject: methods in NSObject. They will perform that method on another object. Now, why would you ever want to do this? Well, you might have some parameterized thing where you’re going to do one of three different methods, depending on something the user chooses. And you can say perform selector and then have three SEL variables, one for each method, and pass that as the argument you want to perform selected.

[obj performSelector:shootSelector];

[obj performSelector:shootAtSelector withObject:coordinate];

#####Using makeObjectsPerformSelector: methods in NSArray You can also do cool thing like ask an array make all the objects in yourself perform this selector. This is a very cool method. And if you get used to using methods like this in Array, you’ll find your code will shrink down really small because, you know, for ins and things like you have to really zoomed down to one-liners, make object perform selector, okay, or make object perform selector with object. So that’s an NSArray thing.

[array makeObjectsPerformSelector:shootSelector]; // cool, huh?

[array makeObjectsPerformSelector:shootAtSelector withObject:target]; // target is an id

And of course, we do target action with selectors. The method, if you wanted to set up target action, not doing control drag but actually setting up in code, is in UI control actually, which button inheritance from:

In UIButton, - (void)addTarget:(id)anObject action:(SEL)action ...;, it says what message to send to what object, what’s the target, what’s the action?

`[button addTarget:self action:@selector(digitPressed:) ...];`

###7. Demo

All right. So let’s take a look at how match – the playing card match – might be improved with introspection. So I’m going to go here back to Xcode. Okay, let’s open Matchismo.xcodeproj and go down to PlayingCard.h and its Counterparts. Look at the match: method:

-(int) match:(NSArray *)otherCards

{

int score = 0;

if ([otherCards count] == 1) {

PlayingCard *otherCard = [otherCards firstObject]; // here

if (otherCard.rank == self.rank){

score = 4;

} else if ([otherCard.suit isEqualToString:self.suit]){

score = 1;

}

}

return score;

}

And here’s the line of code that’s a little bit of trouble. Because the first object here returns an id. So what we could do here, for example:

-(int) match:(NSArray *)otherCards

{

int score = 0;

if ([otherCards count] == 1) {

id card = [otherCards firstObject]; // Changed

if ([card isKind)

PlayingCard *otherCard = ;

if (otherCard.rank == self.rank){

score = 4;

} else if ([otherCard.suit isEqualToString:self.suit]){

score = 1;

}

}

return score;

}

See how we used introspection there? So you have to use introspection most likely in your solution to next week’s homework – not the one you’re currently working on. By the way, I should take time out to say I’d almost – if I ever show you something in a lecture after I’ve assigned something to you, you almost never need it in that week’s homework. And I would tell you if that were the case.

There are two major times when we use introspection – one is this. Second one is all that MVC blind communication. Target action, and delegation, and all that stuff.

###8. Foundation Framework

Now let’s move onto Foundation. I’m going to really go fast through object, Array, dictionary, things like that, because we’ve already seen a lot of Array, I think you pretty much got a good feel for what it is. We got a lot more new stuff to talk about.

#####NSObject

Base class for pretty much every object in the iOS SDK.

Implements introspection methods discussed earlier.

- (NSString *)description is a useful method to override (it’s %@ in NSLog()). It just returns an NSString. And it’s supposed to return a string that describes this object. Okay? When do we ever use this? Two places. One, NSLog. When we’re debugging, we like to NSLog %@. And when we do %@, the matching objects get sent description, and that’s what gets sent out. NSString implements a description by returning self. NSObject implements description very badly. It returns like the pointer, a string with the pointer in it or something. Description becomes valuable when you implement it in your own classes. So you could imagine implementing in playing card or even in card you could implement description that would return self.contents. Right? And then in the debugger there’s a way to print an object in the debugger. It will call description for you and return it. So for card you’d see the contents. So that’s really cool. And the string shows you the string. Arrays and dictionaries implement description to print out the contents of the array. So description’s a really cool little function to know about in NSObject.

Example … NSLog(@“array contents are %@”, myArray);

The %@ is replaced with the results of invoking [myArray description].

#####Copying objects.

This is an important concept to understand (why mutable vs. immutable?).

NSObject kind of implements this framework for copying, but it doesn’t actually implement copy immutable copy. If you look in NSObject, you’ll see that these methods are implemented there or there’s a protocol for them there. Copy and mutable copy are – the semantics of them vary from class to class, so it’s up the class to implement it, okay? Don’t be fooled by the fact that copy and mutable copy are in NSObject. You can’t just send copy to any object and it will copy it. But NSArray, for example, NSDictionary, these things, they implement copy and mutable copy, and they do the right thing. One thing to note about copy is if you send copy to a mutable object like a mutable array, you don’t get a mutable array back, even though you just copied a mutable array. You get an immutable array back, okay? The semantics copy are, “Give me an immutable copy of this object back if possible.” The semantics of mutable copy are, “Give me a mutable copy of this thing.” No matter whether the receiver is mutable or immutable, mutable copy means give me a mutable copy; copy means give me an immutable copy.

- (id)copy; // not all objects implement mechanism (raises exception if not)

- (id)mutableCopy; // not all objects implement mechanism (raises exception if not)

And again, certain classes implement this; NSObject really does not. You would have to implement it yourself if you wanted to have your objects be copyable, which is pretty rare by the way. Really not generaly doing that.

It’s not uncommon to have an array or dictionary and make a mutableCopy and modify that. Or to have a mutable array or dictionary and copy it to “freeze it” and make it immutable. Making copies of collection classes is very efficient, so don’t sweat doing so.

#####NSArray NSArray is an ordered collection of objects. It’s immutable. When you create an NSArray, whatever objects are in it when ou create it, those are the objects that will be in there for life. You can’t remove any, you can’t add any. All objects in an array are held onto strongly in the heap. So as long as that array itself is in the heap, as long as someone has a strong pointer to the array itself, all the objects that are in the array will stay in the heap as well because it has strong pointers to all of them.

You usually create an NSArray by sometimes calling a class method or even alloc init. But usually most commonly we do that @[] thing, like how we created rank strings. Remember rank strings in playing card.

Sometimes we’ll create arrays by asking other arrays to add an object to themselves and give us a new array since they can’t be mutated; they have to make a new one and give it back. You already know these key methods …

- (NSUInteger)count;

- (id)objectAtIndex:(NSUInteger)index; // crashes if index is out of bounds; returns id!

- (id)lastObject; // returns nil (doesn’t crash) if there are no objects in the array

- (id)firstObject; // returns nil (doesn’t crash) if there are no objects in the array

But there are a lot of very interesting methods in this class. You really should familiaize yourself with this class. We talked about make objects perform.

- (NSArray *)sortedArrayUsingSelector:(SEL)aSelector; // [1]

- (void)makeObjectsPerformSelector:(SEL)aSelector withObject:(id)selectorArgument;

- (NSString *)componentsJoinedByString:(NSString *)separator;

[1] So you give it a selector that takes another – that basically gets sent to each object in the array and takes one of the other objects in the array as an argument. So you got to make sure they have the right type of argument there. And it will just use that to create a sorted version of the array and give you back a new array that’s sorted. Okay. So one line of code as long as you have a selector for a method that can compare two objects that are in an array, you can sort it.

#####NSMutableArray NSMutableArray Mutable version of NSArray.

Create with alloc/init or sometimes we use:

+ (id)arrayWithCapacity:(NSUInteger)numItems; // numItems is a performance hint only

+ (id)array; // [NSMutableArray array] is just like [[NSMutableArray alloc] init]

NSMutableArray inherits all of NSArray’s methods. Not just count, objectAtIndex:, etc., but also the more interesting ones mentioned last slide.

And you know that it implements these key methods as well …

- (void)addObject:(id)object; // to the end of the array (note id is the type!)

- (void)insertObject:(id)object atIndex:(NSUInteger)index;

- (void)removeObjectAtIndex:(NSUInteger)index;

#####Enumeration:

Looping through members of an array in an efficient manner

Language support using for-in.

Example: NSArray of NSString objects

NSArray *myArray = ...;

for (NSString *string in myArray) { // no way for compiler to know what myArray contains, and that's essentially your casting, okay? Your casting, whatever comes out of that array to be an NSString.

double value = [string doubleValue]; // crash here if string is not an NSString

}

Example: NSArray of id

NSArray *myArray = ...;

for (id obj in myArray) { // do something with obj, but make sure you don’t send it a message it does not respond to

if ([obj isKindOfClass:[NSString class]]) {

// send NSString messages to obj with no worries

}

}

#####NSNumber

Object wrapper around primitive types like int, float, double, BOOL, enums, etc. And why do you want to wrap them? Usually because you want to put them in Array or a dictionary, okay? So you can’t put an int into an array; you need to have an NSNumber object.

NSNumber *n = [NSNumber numberWithInt:36];

float f = [n floatValue]; // would return 36.0 as a float (i.e. will convert types)

Useful when you want to put these primitive types in a collection (e.g. NSArray or NSDictionary).

New syntax for creating an NSNumber in iOS 6: @()

NSNumber *three = @3;

NSNumber *underline = @(NSUnderlineStyleSingle); // enum

NSNumber *match = @([card match:@[otherCard]]); // expression that returns a primitive type

Any expression that evaluates to a primitive time can be put inside of parenthesis. You say @() and it will create an NSNumber with the result. So other languages kind of have this autoboxing kind of stuff in there.

#####NSValue

NSValue, I’m not going to talk too much about it. It’s essentially a way to encapsulate more complicated types than primitive types, so structs basically, C structs. And NSValue knows how to wrap up a few different kinds of structs that are in iOS. You can go look at the documentations to see which ones. One thing I’m going to give you a little tip right here, okay, sometimes a good way to wrap up a struct is to turn it into a string. Then you can put it in the array as a string. It’s nice because you print it out in the debugger and you can see it really nicely. And then there’s ways to turn things from strings back into C structs. So there are C functions in iOS that turn most of the structs in iOS into string and then other C functions that turn the strings back into the structs. So NSValue – I think most of the time you can use strings. It’s probably more efficient to store something as an NSValue but, again, don’t overoptimize. Turning into a string is just as performant in the case you’re using it. It’s nice because it’s a string and it’s easy to look at.

e.g. NSValue *edgeInsetsObject = [NSValue valueWithUIEdgeInsets:UIEdgeInsetsMake(1,1,1,1)]

Probably don’t need this in this course (maybe when we start using points, sizes and rects).

#####NSData “Bag of bits.” It’s just basically a certain count of bytes. Used to save/restore/transmit raw data throughout the iOS SDK.

######NSDate

NSDate is a date, it has some internal representation. It’s probably the UNIX representation like the number of seconds since 1970 or whatever it is. One thing to think about with NSDates, if you are going to display a date in your UI, make sure you study this in detail (localization). That’s because dates vary dramatically all around the world. And I’m not just talking about in French, you know, the month names are different, but you know, the order of whether the month comes first or the date comes first varies. Some places on earth, some locles don’t even use the same calendar as we use. So there is an enormous amount of infrastructure in iOS for dealing with this. Classes like NSCalendar, and date formatter, and things like that.

Used to find out the time right now or to store past or future times/dates.

#####NSSet / NSMutableSet

There’s NSSet, which a set is an unword collection of objects, so the objects are unique. Set is very good at telling you whether something’s in the set. Whereas an array, if you had an array of a thousand things, the array might have to do some binary searching or well, I guess it can’t even binary search because it doesn’t know the order. But a set is probably hashed and high efficiency.

Like an array, but no ordering (no objectAtIndex: method).

member: is an important method (returns an object if there is one in the set isEqual: to it).

Can union and intersect other sets.

#####NSOrderedSet / NSMutableOrderedSet Sort of a cross between NSArray and NSSet. Objects in an ordered set are distinct. You can’t put the same object in multiple times like array.

#####NSDictionary

This is the second most important collection class behind Array probably.

Immutable collection of objects looked up by a key (simple hash table).

All keys and values are held onto strongly by an NSDictionary. So if they’re in there as a key or a value, then they’re in the heap. And they stay in there as long as the dictionary stays in the heap. The keys and values obviously, are both objects.

Can create with this syntax: @{ key1 : value1, key2 : value2, key3 : value3 }

NSDictionary *colors = @{ @“green” : [UIColor greenColor],

@“blue” : [UIColor blueColor],

@“red” : [UIColor redColor] };

Lookup using “array like” notation …

NSString *colorString = ...;

UIColor *colorObject = colors[colorString]; // works the same as objectForKey: below

- (NSUInteger)count;

- (id)objectForKey:(id)key;

Key must be copyable and implement isEqual: properly. It’s a hash table. You have to be able to hash the key so we can have an efficient lookup. But then tow things might hash to the same thing, so you have to have isEqual: determine whether two objects that hash to the same thing are actually equal. NSObject implements this very poorly, okay? So you would never use a generic object or some subclass of object that you’ve created. You would never use it as a key. You’re probably going to do pointer hashing. So it would only do it if your objects are alwasys unique. In the heap there’s never tow objects that are the same that have different pointers. Strings are excellent keys in NSDictionaries. And so I would say strings are the key in a dictionary 90 percent of the time. NSStrings make good keys because of this.

Of course, NSDictionary is immutable, again.

See NSCopying protocol for more about what it takes to be a key.

#####NSMutableDictionary we’d like to sometimes add things to our dictionaries. Mutable version of NSDictionary.

Create using alloc/init or one of the + (id)dictionary… class methods.

In addition to all the methods inherited from NSDictionary, here are some important methods …

- (void)setObject:(id)anObject forKey:(id)key;

- (void)removeObjectForKey:(id)key;

- (void)removeAllObjects;

- (void)addEntriesFromDictionary:(NSDictionary *)otherDictionary;

#####Looping through the keys or values of a dictionary Example:

NSDictionary *myDictionary = ...;

for (id key in myDictionary) {

// do something with key here

id value = [myDictionary objectForKey:key];

// do something with value here

}

###9. Property List #####The term “Property List” just means a collection of collections This thing I’m going to talk about is not a class, or syntax, or whatever; it’s a word, a phrase – property list. A property list means a “a collection of collections”.

It’s just a phrase (not a language thing). It means any graph of objects containing only: NSArray, NSDictionary, NSNumber, NSString, NSDate, NSData (or mutable subclasses thereof)

So if you have any object graph that just has arrays and dictionaries, numbers, strings, dates and datas, than it’s called a “property list”.

#####An NSArray is a Property List if all its members are too So an NSArray of NSString is a Property List. So is an NSArray of NSArray as long as those NSArray’s members are Property Lists.

But as soon as you have any object in there that’s not one of these things or they’re mutable versions – that’s allowed, too; so you can have NSMutableStrings or NSMutableArrays in there – then it’s not a property list.

#####An NSDictionary is one only if all keys and values are too An NSArray of NSDictionarys whose keys are NSStrings and values are NSNumbers is one.

#####Why define this term?

Because there’s a bunch of API throughout iOS that you’re going to see that takes a property list as the argument. But property list is only phrase we define, so it’s probably going to take an id. It might take an NSArray or an NSDictionary, depending on the API. But it’s basically saying in its documentation, “The argument to this is a property list.”

Usually to read them from somewhere or write them out to somewhere. Example:

- (void)writeToFile:(NSString *)path atomically:(BOOL)atom;

This can (only) be sent to an NSArray or NSDictionary that contains only Property List objects.

###10. Other Foundation

#####NSUserDefaults

I’m going to show you one class that only operates on property lists, which is NSUserDefaults. So NSUserDefaults is this one shared dictionary essentially that persists, even across application launching. Okay? Exiting and launching. So it’s like a permanent NSDictionary kind of.

Everything that’s stored in an NSUserDefault database has to be a property list.

Lightweight storage of Property Lists. Not a full-on database, so only store small things like user preferences.

Read and write via a shared instance obtained via class method standardUserDefaults …

[[NSUserDefaults standardUserDefaults] setArray:rvArray forKey:@“RecentlyViewed”];

That will give you an instance that is shared across your entire application. It’s like a global. Okay? There’s only on of these things.

Sample methods:

- (void)setDouble:(double)aDouble forKey:(NSString *)key;

- (NSInteger)integerForKey:(NSString *)key; // NSInteger is a typedef to 32 or 64 bit int

- (void)setObject:(id)obj forKey:(NSString *)key; // obj must be a Property List

- (NSArray *)arrayForKey:(NSString *)key; // will return nil if value for key is not NSArray

#####Always remember to write the defaults out after each batch of changes!

[[NSUserDefaults standardUserDefaults] synchronize];

A property list, for it to be a property list, everything in the entire object graph has to a property list.

#####NSRange

#####C struct (not a class), Used to specify subranges inside strings and arrays (et. al.).

The last thing really I’m going to talk about that’s kind of in the core part of Foundation is NSRange, which is just a C struct. It’s exactly what you think: It describes a range. This might be a range in a string or it could be a range in an array. It’s basically a starting location, that’s the NSUInteger location and a length – how many characters or how many items in the array?

typedef struct {

NSUInteger location;

NSUInteger length;

} NSRange;

#####Important location value NSNotFound.

There’s an important constant called NSNotFound. NSNotFound is the value of location in a range that was not found or that is otherwise invalid. Okay, so it’s, like, seartch for a substring in a string and it couldn’t find it, you’re going to get range back that the location is going to be NSNotFound.

NSString *greeting = @“hello world”;

NSString *hi = @“hi”;

NSRange r = [greeting rangeOfString:hi]; // finds range of hi characters inside greeting

if (r.location == NSNotFound) { /* couldn’t find hi inside greeting */ }

NSRangePointer (just an NSRange * … used as an out method parameter).

There are C functions like NSEqualRanges(), NSMakeRange(), etc.

Now I told you in iOS we don’t really put structs in the heap and we don’t. This NSRangePointer is for call by reference ranges. So some methods will take an NSRangePointer as an argument – one of its arguments – and what it’s saying there is, “If you pass me a pointer to a range, I’ll fill it in with some information.” Almost always you can pass null there and it won’t fill the information in because you won’t be pointing to a range. But it’s for reference.

###11. Colors We’re going to take a little detour and talk about a couple classes in UIKit. And those are colors and fonts. #####UIColor So UIColor, super simple class, represents a color. The color can be represented in so many different ways, RGB – red, green, blue – HSB, that’s hue, saturation, and brightness. It could even be a pattern. Okay. So you can have a color that is a UI image pattern in there. And when you draw with that color, it will draw with the pattern. So color, super powerful but nice and simple API.

Colors can also have alpha (UIColor *color = [otherColor colorWithAlphaComponent:0.3]).

So alpha, which in computer graphics is how transparent it is – one being fully opaque and zero being fully transparent. You can create colors that are partially transparent. And if you draw with them, you’ll be able to see behind where you filled in. So colors are really cool.

A handful of “standard” colors have class methods (e.g. [UIColor greenColor]).

A few “system” colors also have class methods (e.g. [UIColor lightTextColor], which is the shade of gray for light text, disable text, or whatever.).

###12. Fonts Colors are simple, Fonts, not to simple.

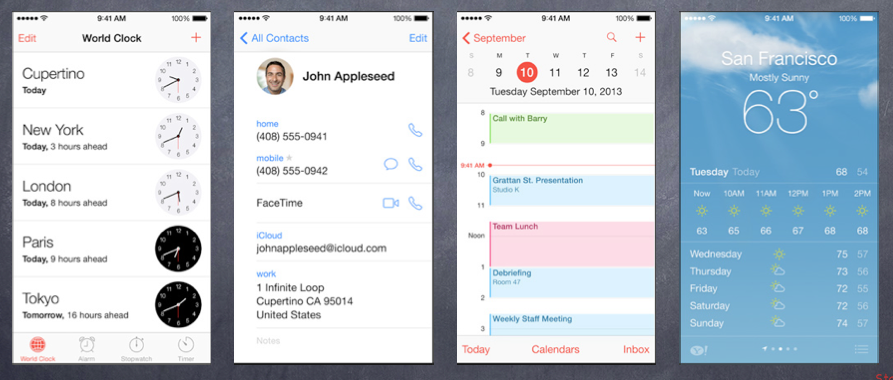

Fonts in iOS 7 are very important to get right. A huge percentage of good iOS 7 UI design is picking the the right fronts, and using fonts in the right way, arranging fonts on screen in a nice way. Super important. So there’s a lot of support in iOS 7 that’s new that is basically about making it easy to do the right thing with fonts. So I put up some examples of some iOS 7 apps here. And you can see how front and center fonts are on all these things.

So color, and background color, and the size of fonts, and all these things are all critically important in all of these applications. So we’re going to talk a little bit about how to deal with this and what’s in there for iOS 7 to make this happen. Unfortunately, I don’t have enough time in lecture in general to go through all of this. I’ll kind of distribute little bits of wisdom about it as we go through various UIs in lecture, and demos, and things like that. What I’m going to try and give you today is just the basis for how we present text on screen, okay? What the premitives are for that and how we do it in the right way so that we get consistency. See, the one thing about all these apps – do you see how the bold font, and the fonts you can click on, and the kind of little subheading fonts, they’re all related fonts, same family – maybe, maybe not. But they’re related. They’re the same sizes. The look the same. So all the apps kind of have a similar look, okay? That’s because they’re all using fonts properly.

#####UIFont

So let’s talk about fonts. The most important thing to understand about fonts is that if you’re displaying user content – okay, that the user’s information. So in the calendar that’s the appointments, and the days of the weeks, and the month, and all those things. In the weather it’s the temperature, and the name of the city, and things like that. In the timer app it’s the city the clocks is in. So if it’s user content – in others words, it’s not the text on a button, okay? Then you want to use a preferred font, what’s called a “preferred font.” And so you want this incredibly important method. If you only learn one method in all of UI font, it’s this iOS 7 method: preferredFontForTextStyle:

UIFont *font = [UIFont preferredFontForTextStyle:UIFontTextStyleBody];

The text style argument is a string. You use a constant that you’re going to look up in UI font descriptor, actually. If you go through UI font, you can link click through and find it. And so there’s the body style. So that’s the text that’s in the body, the main part of what’s being displayed. So like, in an appointment that would be – like in a calenedar item that would be the actual information about what’s going to happen at that appointment.

Some other styles (see UIFontDescriptor documentation for even more styles) . UIFontTextStyleHeadline, UIFontTextStyleCaption1, UIFontTextStyleFootnote, etc. There’s about, I think, eight or so of these. And you should familiarize yourself with what circumstances semantically those things should be used in. And then when you want a font in your app, you should be using one of these. Okay? For user content.

There are also “system” fonts. These are what goes on buttons. They are used in places like button titles.

+ (UIFont *)systemFontOfSize:(CGFloat)pointSize;

+ (UIFont *)boldSystemFontOfSize:(CGFloat)pointSize;

You should never uses these for your user’s content. Sometimes it’s okay to use a preferred font on a button. It depends on whether the title of the button might change, depending on user’s content. Basically it’s the user’s content on a button. That would be okay. But you generally wouldn’t want to use system fonts for user’s content.

Use preferredFontForTextStyle: for that.

#####UIFontDescriptor Fonts are designed by artists. They aren’t always designed to fit any sort of categorization. Some fonts have Narrow or Bold or Condensed faces, some do not. Even “size” is sometimes a designed-in aspect of a particular font. A designer of a font will design a larger S with a little more curve here and there than a smaller S. Okay? Size is not just a matter of vector graphic zooming in and out – sometimes, it depends on the font.

So UI font descriptor’s new in iOS 7. It attempts to put categories on fonts that defy categoriztion. So the UI font descriptor has a lot of knowledge in it about faces and is there a bold version of this, is there a condensed version, is there an italic version? And so it maps that into something we, as computer cientists, want to do because we want to put something in bold on the screen. Okay? So that’s UI font descriptor is all about.

A UIFontDescriptor attempts to categorize a font anyway.

It does so by family, face, size, and other attributes.

You can then ask for fonts that have those attributes and get a “best match.”

Understand that a best match for a “bold” font may not be bold if there’s no such designed face.

#####UIFontDescriptor(Did not mention in the lecture, but in slides) You can get a font descriptor from an existing UIFont with this UIFont method:

- (UIFontDescriptor *)fontDescriptor;

You might well have gotten the original UIFont using preferredFontForTextStyle:.

Then you might modify it to create a new descriptor with methods in UIFontDescriptor like:

- (UIFontDescriptor *)fontDescriptorByAddingAttributes:(NSDictionary *)attributes;

(the attributes and their values can be found in the class reference page for UIFontDescriptor) You can also create a UIFontDescriptor directly from attributes (though this is rare) using :

+ (UIFontDescriptor *)fontDescriptorWithFontAttributes:(NSDictionary *)attributes;

#####Symbolic Traits Italic, Bold, Condensed, etc., are important enough to get their own API in UIFontDescriptor:

- (UIFontDescriptorSymbolicTraits)symbolicTraits;

- (UIFontDescriptor *)fontDescriptorWithSymbolicTraits:(UIFontDescriptorSymbolicTraits)traits;

Some example traits (again, see UIFontDescriptor documentation for more):

UIFontDescriptorTraitItalic, UIFontDescriptorTraitBold, UIFontDescriptorTraitCondensed, etc.

Once you have a UIFontDescriptor that describes the font you want, use this UIFont method:

+ (UIFont *)fontWithDescriptor:(UIFontDescriptor *)descriptor size:(CGFloat)size;

(specify size of 0 if you want to use whatever size is in the descriptor) You will get a “best match” for your descriptor given available fonts and their faces.

#####Example Let’s try to get a “bold body font”:

UIFont *bodyFont = [UIFont preferredFontForTextStyle:UIFontTextStyleBody];

UIFontDescriptor *existingDescriptor = [bodyFont fontDescriptor];

UIFontDescriptorSymbolicTraits traits = existingDescriptor.symbolicTraits;

traits |= UIFontDescriptorTraitBold;

UIFontDescriptor *newDescriptor = [existingDescriptor fontDescriptorWithSymbolicTraits:traits];

UIFont *boldBodyFont = [UIFont fontWithFontDescriptor:newDescriptor size:0];

This will do the best it can to give you a bold version of the UIFontTextStyleBody preferred font. It may or may not actually be bold.

###12. Attributed Strings

So now let’s talk about how text looks on screen.

######How text looks on screen

The font has a lot to do with how text looks on screen. Depending on which font you pick, that’s going to determine a lot of what it looks like.

But there are other determiners (color, whether it is “outlined”, stroke width, underlining, etc.). You put the text together with a font and these other determiners using NSAttributedString.

#####NSAttributedString Think of it as an NSString where each character has an NSDictionary of “attributes”. The attributes are things like the font, the color, underlining or not, etc., of the character. It is not, however, actually a subclass of NSString (more on this in a moment). You cannot send it string messages. So that seems like a significant restriction.

It’s immutable,not modifiable. So you cannot set the attributes of an NSAttributedString. There is a mutable sttributed string, we’ll talk about that in a second.

#####Getting Attributes You can ask an NSAttributedString all about the attributes at a given location in the string.

- (NSDictionary *)attributesAtIndex:(NSUInteger)index

effectiveRange:(NSRangePointer)range;

The range is returned and it lets you know for how many characters the attributes are identical. There are also methods to ask just about a certain attribute you might be interested in. NSRangePointer is essentially an NSRange *. It’s basically just telling you how many characters have the attributes you asked for at that character. It’s okay to pass NULL if you don’t care.

#####NSAttributedString is not an NSString It does not inherit from NSString, so you cannot use NSString methods on it. If you need to operate on the characters, there is this great method in NSAttributedString …

- (NSString *)string;

This will return an NSString that you can then search in or do all the string things you want.

For example, to find a substring in an NSAttributedString, you could do this …

NSAttributedString *attributedString = ...;

NSString *substring = ...;

NSRange r = [[attributedString string] rangeOfString:substring];

The method string is guaranteed to be high performance but is volatile. The bottom line is this thing is probably returning you a pointer to that NSAttributedString’s internal data structure. If you want to keep it around, make a copy of it. You almost never need to do that because you’re almost always operating on the string right there in place this – a range of string.

#####NSMutableAttributedString Unlike NSString, we almost always use mutable attributed strings. It inherit from the nonmutable attributed string. But it’s not an NSString or an NSMutableString. It’s an NSAttributedString.

####Adding or setting attributes on the characters You can add an attribute to a range of characters …

- (void)addAttributes:(NSDictionary *)attributes range:(NSRange)range;

which will change the values of attributes in attributes and not touch other attributes. Or you can set the attributes in a range:

- (void)setAttributes:(NSDictionary *)attributes range:(NSRange)range;

which will remove all other attributes in that range in favor of the passed attributes. You can also remove a specific attribute from a range:

- (void)removeAttribute:(NSString *)attributeName range:(NSRange)range;

Modifying the contents of the string (changing the characters) You can do that with methods to append, insert, delete or replace characters.

Or call the NSMutableAttributedString method - (NSMutableString *)mutableStringand modify the returned NSMutableString (attributes will, incredibly, be preserved!).

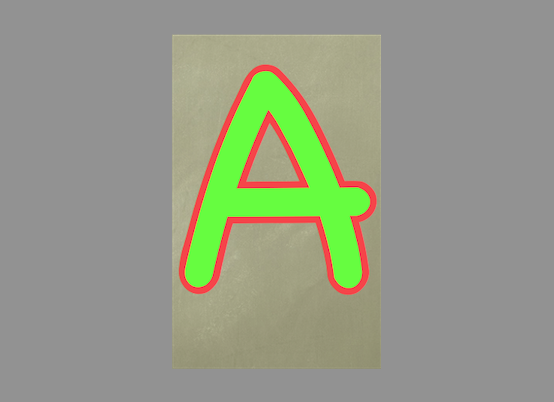

#####So what kind of attributes are there?

One of the big ones is the font. So this is a dictionary.

UIColor *yellow = [UIColor yellowColor];

UIColor *transparentYellow = [yellow colorWithAlphaComponent:0.3];

@{ NSFontAttributeName :

[UIFont preferredFontWithTextStyle:UIFontTextStyleHeadline]

NSForegroundColorAttributeName : [UIColor greenColor],

NSStrokeWidthAttributeName : @-5,

NSStrokeColorAttributeName : [UIColor redColor],

NSUnderlineStyleAttributeName : @(NSUnderlineStyleNone),

NSBackgroundColorAttributeName : transparentYellow }

The key for the font is NSFontAttributeName.And the value of that is a UIFont. So this is where you would get a preferred font of a certain style, like a headline, let’s say, in this case.

You can look up these keys by going and looking – if you look up NSAttributedString in the documentation, there’s a link there, which is UIkit additions to NSAttributedString, and all the keys that I’m going to talk about are there.

Be a little careful when you create an attributed string that has colored text because in iOS 7 the color of text sometimes is an indictor to the end user what they can touch.Be Consistent.

There’e also stroke with attribute and stroke color. The with attribute – and pay attention to this because you’ll need this probably for your homework – it’s an NSNumber. If it’s a negative NSNumber, then that means fill glyph, you know, the A fill it, and stroke around the edge. If it’s a positive number, it means just do the stroke around the edge and the middle is transparent.

Underline style attribute name. So that’s an NSNumber that has an e num. There’s also background color.

#####So where do we use attributed string?

UIButton’s - (void)setAttributedTitle:(NSAttributedString *)title forState:...;

UILabel’s @property (nonatomic, strong) NSAttributedString *attributedText;

UITextView’s @property (nonatomic, readonly) NSTextStorage *textStorage;

UITextView is like a UILabel, but it’s editable, selectable, scrollable, etc.

#####UIButton Attributed strings on buttons will be extremely use for your homework.

#####Drawing strings directly on screen Next week we’ll see how to draw things directly on screen. NSAttributedStrings know how to draw themselves on screen, for example …

- (void)drawInRect:(CGRect)aRect;

Don’t worry about this too much for now. Wait until next week.

###13. UILabel UILabel has a property, it’s an NSAttributedString called “attributed text.” It’s just like the text label, which is an NSString, which we’ve already used in this class. You have been setting its contents using the NSString property text. But it also has a property to set/get its text using an NSAttributedString …

@property (nonatomic, strong) NSAttributedString *attributedText;

#####Note that this attributed string is not mutable So, to modify what is in a UILabel, you must make a mutableCopy, modify it, then set it back.

NSMutableAttributedString *labelText = [myLabel.attributedText mutableCopy];

[labelText setAttributes:...];

myLabel.attributedText = labelText;

Don’t need this very often There are properties in UILabel like font, textColor, etc., for setting look of all characters. The attributed string in UILabel would be used mostly for “specialty labels”.

###Next Time.

- Location and Time

- Debugging

- Xcode Tips and Tricks

and next:

- UITextView

- NSNotification (radio station)

- Demo of Attributed Strings, etc.

- View Controller Lifecycle

###Lecture 5 done!